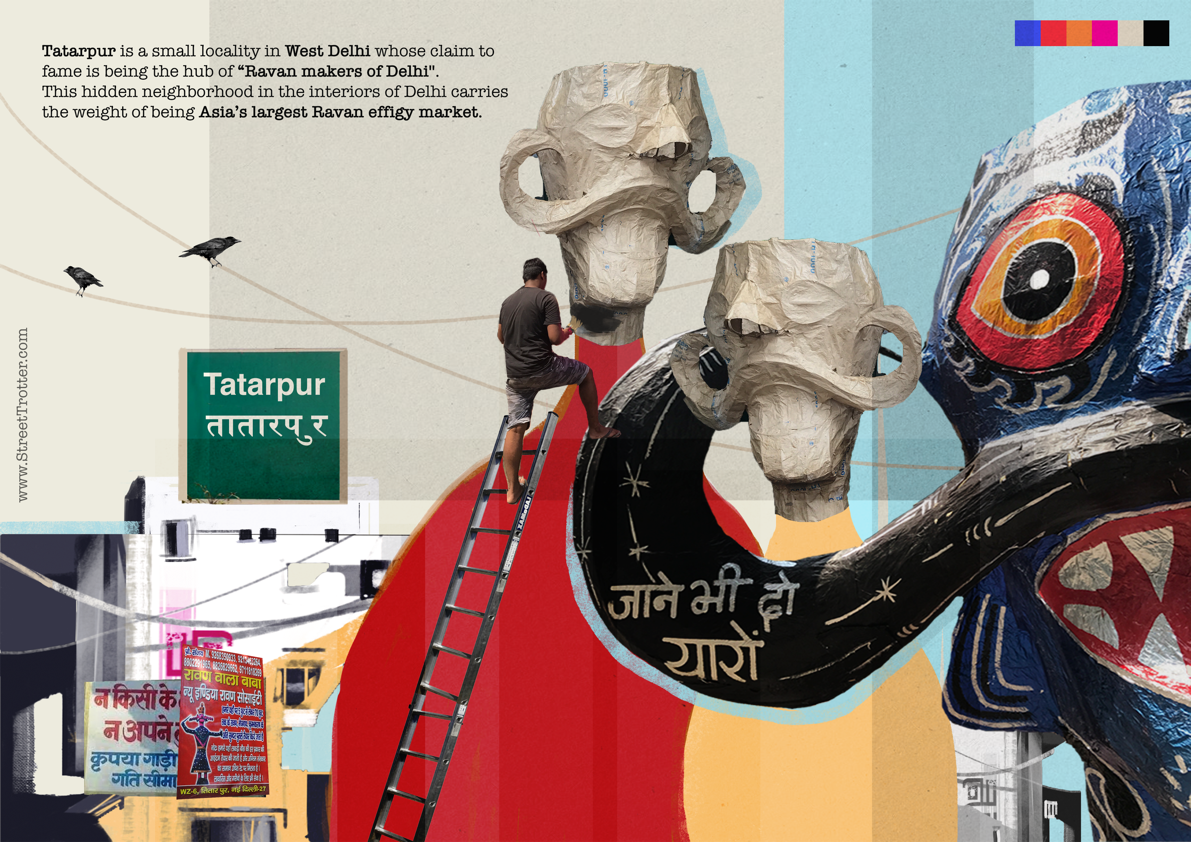

A line of effigies shaped in bamboo in the form of humongous heads, giant mustaches, and fearsome eyes, lie around on an open road. Some are ready to be painted, some are getting their finishing touches, while others are all decked up to be assembled. Besides the heads are huge structures of limbs and torsos that range from a few feet to about three or four storeys high. These effigy parts lying around are of the mythical demon king of Lanka, ‘Ravana’ in Hindu mythology. And the place we are describing is popularly known as the “Lanka of Delhi”, ‘Tatarpur’.

Tatarpur is a small village in West Delhi whose claim to fame is being the hub of “Ravan makers of Delhi”. This hidden neighbourhood in the interiors of Delhi carries the weight of being Asia’s largest Ravan effigy market.

‘The Ravanwalas of Tatarpur’ – as the craftsmen are called – are a mixed crowd of the original artisan community and temporary workers who come from different parts of Delhi and Uttar Pradesh during the months of August, September, and October to earn some extra money. During these months, the artisans are sprawled across the roads, working on crafting Ravan effigies of various sizes that are an integral part of celebrating one of the biggest Hindu festivals of India, Dussehra.

Celebrated in the month of October, Dussehra marks the victory of good over evil. The elaborate celebrations mostly spread across North India, consist of acting out scenes from the oldest Indian epic Ramayana. And the big showdown is with the three great effigies (of Ravana, Meghnad and Khumbhakarna), being burnt to flames by shooting flaming arrows at them – an act called Ravan Dahan.

The legend of Ravana and the festival

The story of Ravana from theepic of Ramayana is an integral part of India’s mythological tales. Also referred to as Lankeshwar, he is pictorially depicted as having ten heads and twenty arms, with a fearsome appearence. But Ravana is also a character that is clouded with myths. He is shown as a demon king of pure evil on one hand, but a devout worshipper of Brahma and an artist on the other. The legend of Ravana playing the Rudraveena and his lifelong penance to Lord Shiva makes him a difficult character to judge.

One of the most fascinating facts of Ravana’s image is that his ten heads are symbolic of the 6 Shastras (Sankhya, Yoga, Nyaya, Mimamsa, and Vedanta) and 4 Vedas (Rig Veda, Sama Veda, Yajur Veda, and Atharva Veda) of Hinduism – that present him as a great scholar. Alternatively, they also symbolise the dark facets of him and his arrogance that paved the way for his downfall.

But the story of Dussehra is not so much about Ravana as it is about the victory of Lord Rama. As the tale of Ramayana narrates, Rama – his wife Sita, and brother Lakshmana were exiled for 14 years. In a tragic turn of events, Sita was abducted by Ravana and taken to Lanka. The great epic follows the story of Rama, his loyal brother Lakshmana and his army of Vanaras (most often characterized as an army of monkeys), who set out on a mission to free Sita.

The ground where Dussehra is celebrated is called the ‘Ramleela Maidan’ and three effigies are burnt down on the day of the celebrations. The three effigies are of Ravana, his son Meghnad and his brother Kumbhakarna. Rama and Lakshman killed Meghnad and Khumbhakarna respectively. But the main story remains that of the epic battle between Rama and Ravana where Rama emerges victorious after a fierce fight with the king of Lanka, thus bringing Sita back home.

The making of effigies throughout a sustainable process

The giant effigies of Ravana are painstakingly made by the artisans in Tatarpur every year and the process itself is a reminder of an old yet fascinating local craft of India. In fact, what is often overlooked is that it is also a sustainable craft that uses eco-friendly materials and processes.

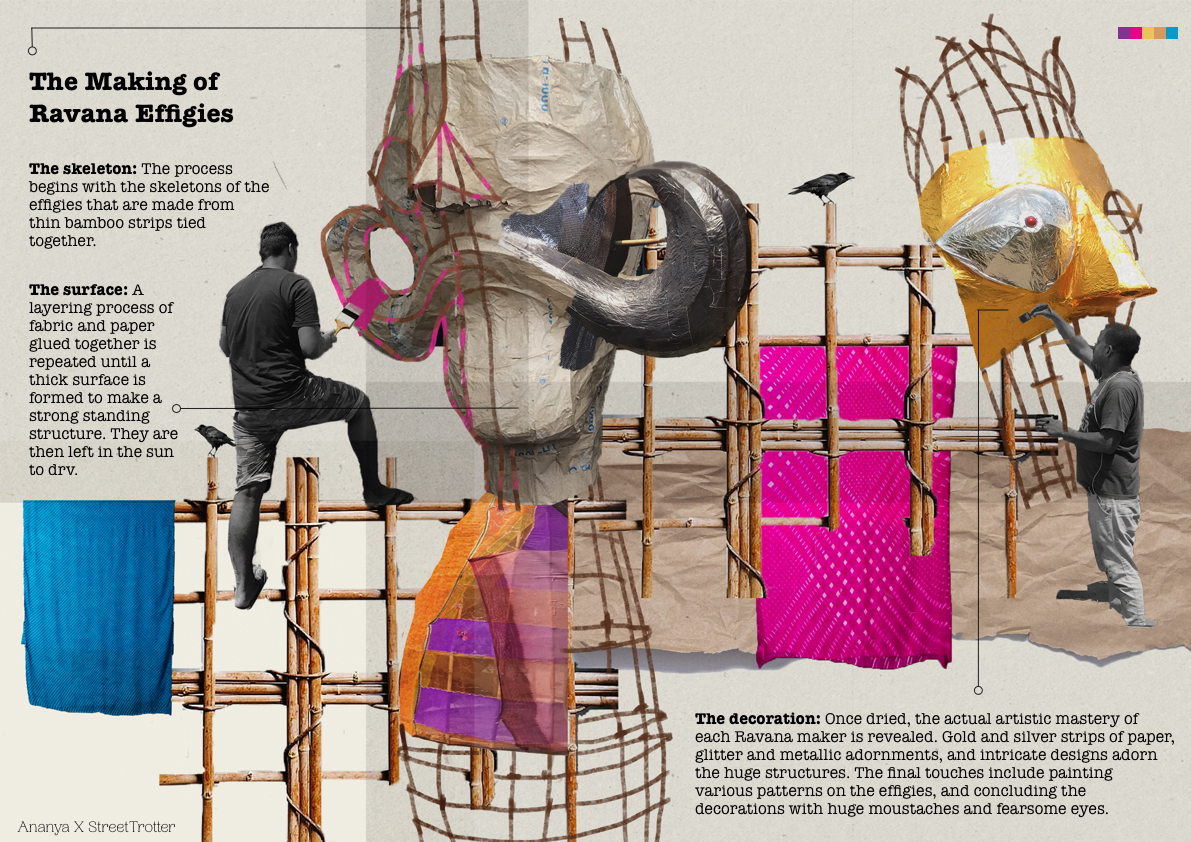

The skeleton: Each complete effigy is made in different parts that are later attached in a process that is called Napai. The process begins with the skeletons of the effigies that are made from thin bamboo strips tied together. This makes the frame of the head, limbs or torso. The torsos itself are long cylindrical structures that are then wrapped with alternating layers of old sarees and thick sheets of brown paper – stuck together using a natural paste of sugar and cornflour mixed to become glue.

The surface: The sarees (used as fabric) are usually discarded chiffon sarees that are bought in bulk as recycled fabric from the Sadar Bazaar of North Delhi. This layering process of fabric and paper is repeated until a thick surface is formed to make a strong standing structure. These structures are then either painted with different kinds of vibrant colours or wrapped in colourful papers that determine the appearance of the Ravana.

Once wrapped and ready, these structures are further kept in the sun to dry. It takes up a lot of space to dry these huge effigies, and therefore they are kept in open spaces such as on-road pavements, dividers, and public parks – spread all across Tatarpur.

The decoration: Once dried, the actual artistic mastery of each Ravana maker is revealed. Gold and silver strips of paper, glitter and metallic adornments, and intricate designs adorn the huge structures. The final touches include painting various patterns on the effigies according to the orders placed by the customers.

Various types of effigies are found in and around the area. While some have moustaches that are two feet long, others have designs dominated by silver and golden colours painted all over them.

During the festive season, Tatarpur seems to have every fluorescent and vibrant colour present in these effigies and become a sight to behold for anyone who visits the place. From dwarf effigies to the giant ones that have to be assembled by several people – the variety is unimaginable.

The assembly: It takes nine to ten people to measure each part of the effigies. The final assembly of the parts is done in places outside of Delhi, like Moradabad, Hapur, and Ghaziabad. The total height of the effigies ranges from seven to seventy and as far as 150 to 200 feet. This indicates the enormous amount of work that is put in by the workers who come to Tatarpur, and also the grandness of the craft for a curious spectator.

The surplus: After Dussehra is over, the unsold effigies are not discarded. They are dismantled and recycled instead. The cane frames are used by carpenters to make other items of utility like small-sized furniture. The paper used is also recycled and reused.

The unique image and evolution of the effigies

As one takes a walk through the streets of Tatarpur, it’s easy to notice a variety of designs that make each effigy stand apart from the other – depending on the artists who have made them. Large eyes, expressions of mockery, excitement, and even sadness can be seen in the many heads that line up. Some craftsmen believe that the soul of every effigy lies in its eyes and how the eyes should evoke the fear of Ravana.

The uneven teeth and multiple strands of moustaches add to the final detail of the demon’s fearsome appearance. All these features are often the defining factors of the craftsman himself and also a reflection of his personal expression. What makes observing the evolution of this craft even more interesting is the fact that the final effigies of the Ravans are dynamic which keep changing each year reflecting the spirit of the times. Like every other form of art, the craft itself has been adapting, affected by socio-economic and cultural changes. Over the last decade, one can notice the variations in the styles of Ravans like the different designs of earrings and the occasional sunglasses on the eyes.

A significant cultural influence was during the anti-corruption movement of 2011. The Ravans were made with ‘Corruption’ written on them and burning them symbolised the burning of evil at the time, i.e. the issue of corruption. Societal influences can also be found in the many dialogues of Bollywood movies that are written on the effigies.

Another significant evolution of the craft today came with the recent firework ban In India. When the firework ban was imposed in Delhi in 2019, it was to affect the Dussehra celebrations as well, since they are an integral part of the festival. But this sustainable craft of the Ravan-makers adapted to this change in their own way. The effigies are not filled with firecrackers any longer. This is compensated by the sound of crackers playing in speakers.

A little more about the Ravanwalas

The Ravan-making community of Tatarpur is a mixed crowd of permanent residents who have been practicing the craft for ages and temporary helpers who flock to this cluster when they are needed. Together, all craftsmen of Tatarpur start working on the effigies as early as the month of June every year. Each effigy is sold at a price ranging from Rs. 5,000 to Rs, 25,000 on an average with orders coming in locally from India as well as overseas such as the US.

For the families that have been practicing the craft for generations, one can easily spot the most experienced ones who have been a part of the Ravan-making community for over 60 years, tutoring the younger ones to pass on their skills in an attempt to keep the craft alive over time.

And even though the mythological character of Ravana himself is often depicted as the evil, it has become a sense of identity for the residents of Tatarpur. For the same reason, the Ravan makers refuse to watch the grand Ravan burning ceremony that is otherwise seen as the primary event of any Dussehra celebration.

Primary research by: Abhinandita Dev | Secondary research & Authored by: Sarasi Ganguly | Artworks by: Ananya S R | Concept & Photography: Shraddha Gupta